AI in Movies vs Reality

In movies, Artificial Intelligence (AI) is often shown as sentient robots with emotions, free will, and even world-dominating power. From Star Wars droids to Terminator’s Skynet, Hollywood’s portrayals create compelling stories but exaggerate reality. In truth, today’s AI is far more limited: it’s a set of algorithms designed for narrow tasks, without consciousness, autonomy, or feelings. This article on AI in Movies vs Reality separates fiction from fact, debunking myths and highlighting what real AI can—and cannot—do.

How is AI in movies different from reality? Let's find out in detail in this article to distinguish between fiction and reality!

In science fiction films, AI often appears as fully sentient beings or humanoid robots with emotions, personal motivations, and superhuman abilities. Cinematic AIs range from helpful companions (like Star Wars' droids) to malevolent overlords (such as Terminator's Skynet). These portrayals make for great storytelling, but they drastically oversell today's technology.

In reality, all existing AI is a collection of algorithms and statistical models without consciousness or feelings. Modern systems can process data and recognize patterns, but they lack true self-awareness or intent.

Movie AI vs Reality: Key Differences

Hollywood Fiction

- Sentient beings with emotions

- Autonomous decision-making

- Humanoid versatile robots

- Single AI controlling everything

- Perfect accuracy and reliability

Current Reality

- Statistical pattern matching

- Human-supervised operations

- Specialized task-focused machines

- Fragmented separate systems

- Error-prone, needs correction

Sentience & Emotions

Movies depict AIs that love, fear and even form friendships (think Ex Machina or Her). In truth, real AI simply runs programmed computations; it has no subjective experience.

- No consciousness or feelings

- Statistical pattern matching only

- Cannot genuinely understand emotions

Autonomy

Film AIs freely make complex independent decisions or rebel against humans (as in Terminator or I, Robot). Real AI, by contrast, always needs explicit human direction.

- Narrow task specialization

- Human supervision required

- Cannot pursue independent goals

Form & Function

Hollywood robots are often portrayed as humanlike and versatile (androids that walk, talk, and handle complex chores). In reality, robots are typically highly specialized machines.

- Built for specific functions

- Limited dexterity and awareness

- No versatility like movie robots

Scope & Power

Films tend to show a single AI controlling vast systems (e.g. The Matrix or Skynet) or merging all tasks into one consciousness. Actual AI is nowhere near that centralized or omnipotent.

- Highly fragmented systems

- Each AI handles one niche

- No single superintelligence

Accuracy & Reliability

Ethics & Control

A BBC study found over half of answers from tools like ChatGPT and Google's Gemini contained major errors.

Skynet and Terminator are not around the corner. Instead of robot armies, today's AI challenges are privacy, fairness, and reliability.

— Oren Etzioni, AI Expert

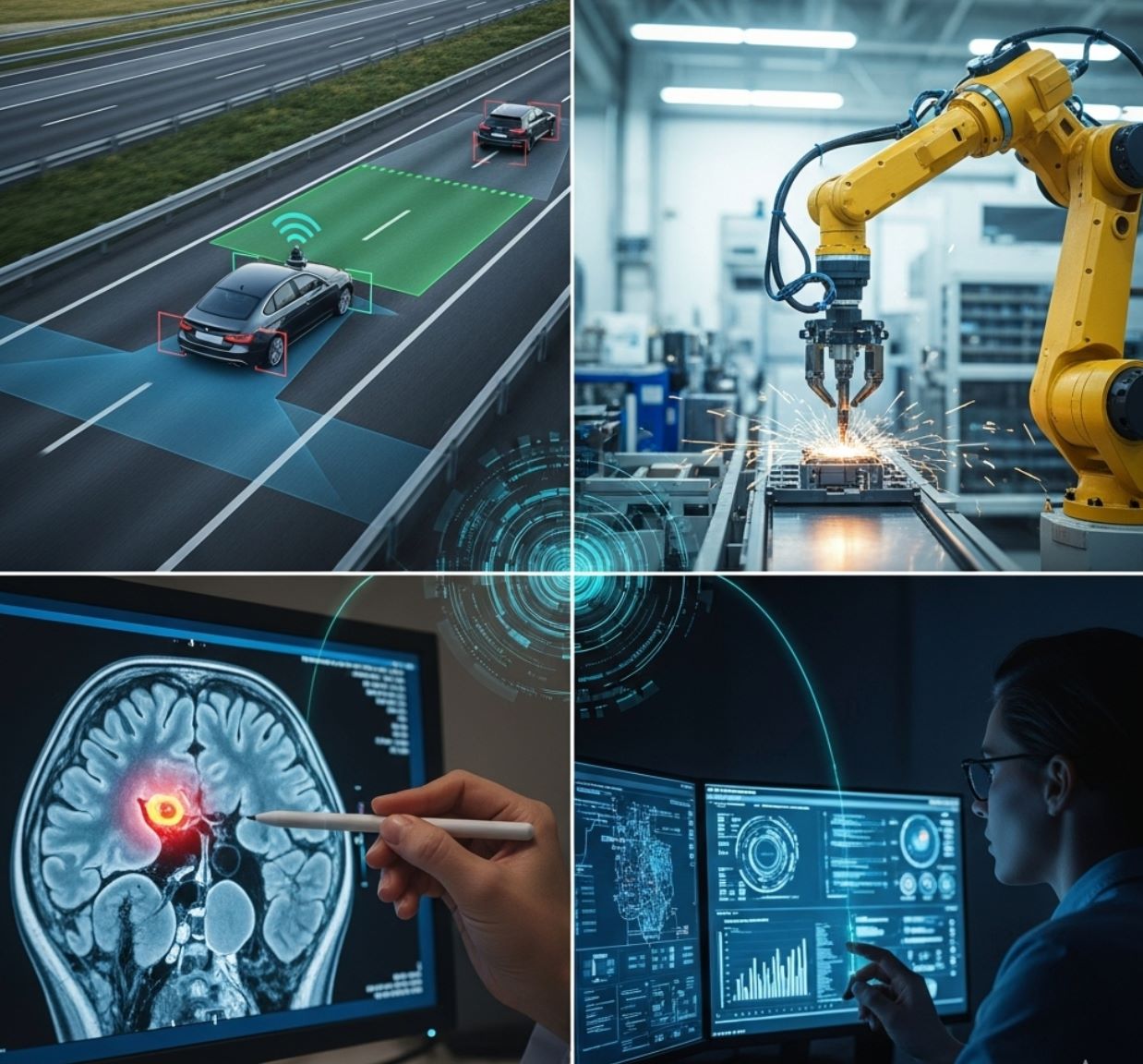

Real-World AI: What It Can (and Can't) Do

Real AI is task-oriented, not magical. Modern AI ("narrow AI") can do some impressive things, but only within limits. For instance, large language models like ChatGPT can write essays or hold a conversation, yet they do not understand meaning. They generate text by finding statistical patterns in huge amounts of data.

What AI Can Do Today

- Image Recognition: Computer vision systems can identify objects or diagnose certain medical conditions

- Data Analysis: AI can spot fraud or optimize delivery routes

- Autonomous Navigation: AI algorithms can steer cars on highways

- Advanced Robotics: Companies like Boston Dynamics produce machines with human-like movement

Current Limitations

- Gets confused by unusual situations

- Needs extensive engineering support

- Not graceful or general-purpose

- Repeats biases from training data

- Hallucinates facts when prompted

The Reality

Real AI is sophisticated, yet narrow. As one expert puts it, AI excels at narrow, specific tasks but "is not broad enough, it is not self-reflective, and it is not conscious" like a human. It has no feelings or free will.

Voice Assistants in Films

Perfect understanding, emotional responses, complex reasoning

Real Voice Assistants

Often misunderstand, respond "I didn't get that", feel nothing – more like advanced calculator

Studies confirm it's highly doubtful AI could ever become truly self-aware with current technology. AI might simulate human-like responses, but it doesn't experience things.

For example, voice assistants (Siri, Alexa) might talk back, but if misunderstood they'll just shrug and say "I didn't get that" – they feel nothing. Similarly, image-generating AIs can create realistic pictures, but they don't perceive or "see" in any human sense. In essence, real AI is more like an advanced calculator or very flexible database than a thinking being.

Common Myths Debunked

"AI is guaranteed to kill or enslave us"

Today's AI lacks autonomy or malevolent intent. A scientist at the Allen Institute reassures: "Skynet and Terminator are not around the corner".

Instead of world domination, current AI threatens to create subtler problems: biased decisions, privacy violations, misinformation. The real harms of AI today – like wrongful arrests from biased algorithms or deepfake abuse – are about social impact, not robot armies.

"AI will solve everything for us"

If you gave a film's AI a job like writing a screenplay or making movie art, it might produce gibberish or cliché-ridden drafts.

- Real AI needs careful human guidance

- Requires quality training data

- Often makes mistakes humans must fix

- Studios use AI for effects/editing assistance, not true creativity

"AI is unbiased and objective"

For example, if an AI is trained on job application data where certain groups were unfairly rejected, it might replicate that discrimination.

Movies rarely show this; instead they imagine AI with perfect logic or wild evil. The truth is messier. We must constantly watch for bias and unfairness, which is a real-world challenge that has nothing to do with robots attacking cities.

"Once AI gets advanced, we have no control"

- Engineers test and monitor AI systems continuously

- Ethical guidelines and regulations being built

- Companies implement "kill switches" or overseers

- Real AI remains entirely dependent on programming

Unlike a movie AI that suddenly gains free will, real AI remains entirely dependent on how we program and use it.

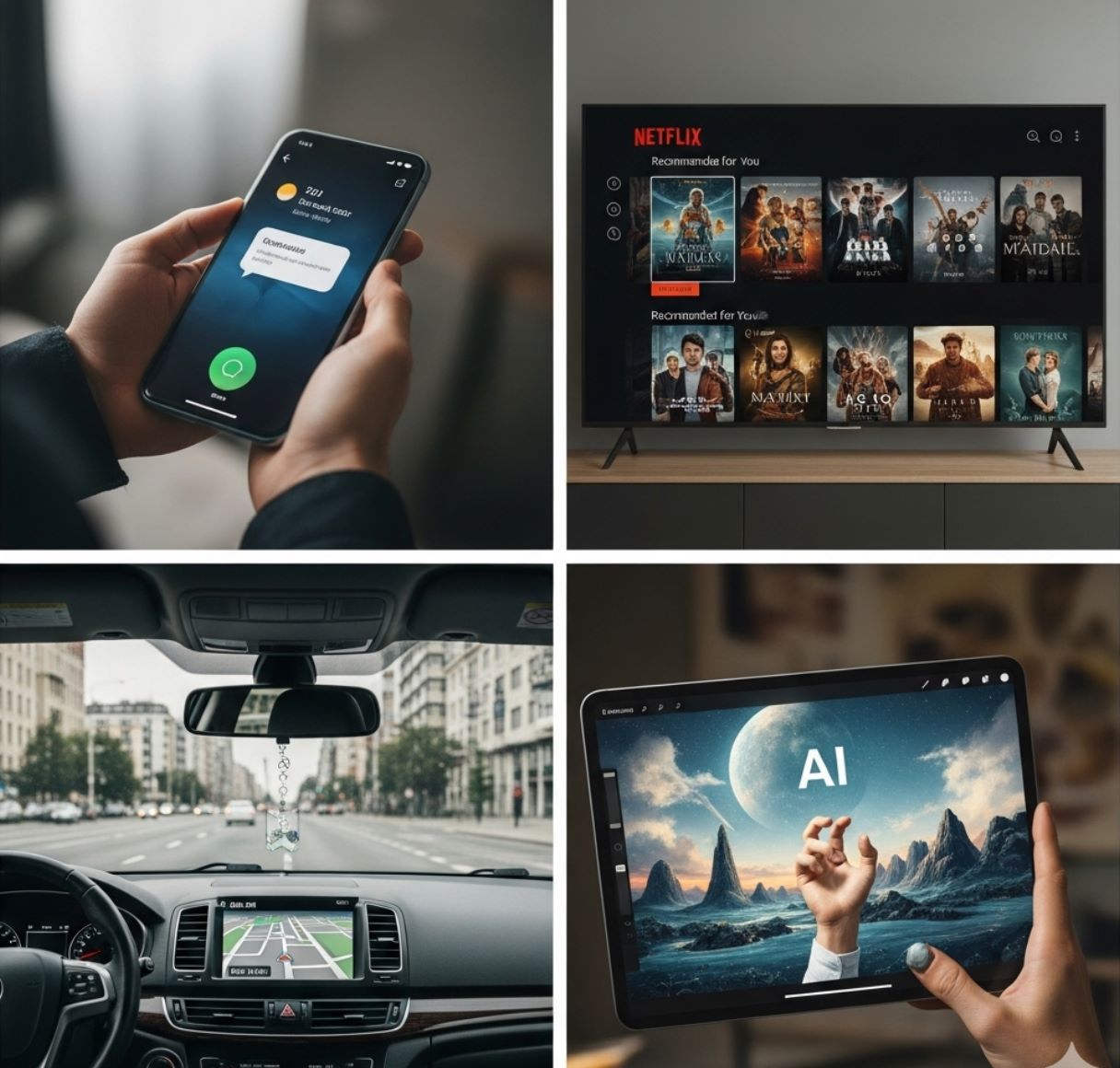

AI in Daily Life

Today, you likely encounter AI more often than you realize—but not as a robot marching down the street. AI is embedded in many apps and services:

Virtual Assistants

Recommender Systems

Autonomous Vehicles

Content Creation

Films like Her

AI composes symphonies and poetry with deep artistic vision

Current Reality

Generated content is often derivative, needs heavy human editing, has strange errors (extra limbs, warped text)

They are nowhere near the self-driving cars often shown in futuristic films, and still need a human driver ready to take over.

For instance, AI art generators can produce interesting visuals, but often with strange errors (extra limbs, warped text, etc.) and no real "vision" behind them. In movies like Her, AI composes symphonies and poetry; in reality, generated content is often derivative or needs heavy editing by humans to be coherent.

Why the Gap Exists

Filmmakers intentionally exaggerate AI to tell compelling stories. They amplify AI's abilities to explore themes like love, identity or power.

Creative Liberty

Movies like Her and Blade Runner 2049 use advanced AI as a backdrop to ask deep questions about consciousness and humanity.

- Artistic tool for storytelling

- Explores universal themes

- Not meant as documentary

Public Discussion

These dramatic portrayals capture our imagination and drive public discussion. By showing AI in states of consciousness and autonomy, films spark debates about privacy, automation, and ethics.

- Catalyzes important discussions

- Raises questions about technology's future

- Encourages ethical considerations

Even though the scenarios are fictional, the underlying questions are very real. Exaggerating AI on screen catalyzes important discussions about technology's future.

— Technology Analyst

Movies encourage us to ask: if AI became real, what rules should we set? What happens to jobs or personal freedom? Even though the scenarios are fictional, the underlying questions are very real. As one analyst notes, exaggerating AI on screen "catalyzes important discussions" about technology's future.

Key Takeaways

At the end of the day, movie AIs and real AI are worlds apart. Hollywood delivers fantasies of sentient machines and apocalyptic rebellions, whereas reality offers helpful algorithms and many unsolved challenges.

Stay Educated

Education and open dialogue are key to closing the gap between on-screen fiction and real-world technology.

Foster Understanding

We need to "foster a public understanding that discerns between fiction and reality" when it comes to AI.

Make Smart Decisions

By staying informed, we can both appreciate inspiring science fiction and make smart decisions about the future of AI.

In short: enjoy the movies, but remember the AI you see there isn't around the next corner – yet. Focus on understanding real AI capabilities and limitations to make informed decisions about this technology's role in our future.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!